The book, Smart but Scattered by Richard Guare and Peg Dawson defines the Executive Function skill of Working Memory as: The ability to hold information in memory while performing complex tasks. It incorporates the ability to draw on past learning or experience to apply to the situation at hand or to project into the future. The significance here lies in the ability to hold information in the memory FROM previous learning schema while performing complex tasks to apply the learning to a future project or learning that may or may not have the same qualities required from an earlier learned concept but can approach with the sieved information.

In light of how layered and fast-paced the interactions can be with the push toward generated artificial intelligence, from person-to-person output to productive work, the academic, lab-defined working memory which we are all used to as expressed by Smart but Scattered are influenced by numerous societal factors, and a shift in demands. Let’s begin to explore here what first is and has remained the same with the development of working memory before delving into what is new.

Researchers Cheng, C., & Kibbe, M. M. (2024). conducted a study on Children’s use of reasoning by exclusion to infer objects’ identities in working memory. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 237, 105765. They emphasize that to achieve cognitive goals in the face of incomplete information, a learner can use logical reasoning to make inferences about what they don’t know based on what is already known. Reasoning by exclusion therefore is a powerful means of resolving representational uncertainty without needing to exert excess physical effort (such as walking over to the other dish and lifting the lid) to do so. Successful reasoning by exclusion requires children to rely on working memory, however, their working memory is severely capacity-limited and undergoes substantial developmental increases in capacity between infancy and late childhood (Cheng and Kibbe, 2022, Cowan, 2001, Cowan, 2016, Cowan et al., 2015, Kibbe, 2015, Leslie et al., 1998, Pailian et al., 2016, Simmering, 2012).

On the one hand, the ability to reason by exclusion about uncertain/unknown object locations or identities may impose greater demands on working memory than simply storing representations of a known array of items. This is because reasoning by exclusion tasks often require children to store uncertain or unknown representations in working memory, and then update those representations once they receive the relevant disambiguating information. The researchers also claim that the reasoning-by-exclusion process itself may incur some cognitive cost above and beyond the costs of updating working memory because children may need to expend cognitive effort to make inferences about unknown information from known alternatives. Inferring unknown object properties from known alternatives therefore may be more demanding and more error-prone than storing known information in working memory, and as the working memory load increases children’s reasoning by exclusion abilities may be more limited, creating an inverse relationship the younger the child. Under this possibility, reasoning by exclusion might not impose significant additional demands on working memory, and reasoning by exclusion should not be negatively affected by increasing working memory load (or indeed, reasoning by exclusion may even become more reliable as working memory is taxed), and we would be unlikely to see improvements in reasoning by exclusion abilities as working memory capacity increases with development and age.

What we would model for children even in this hyper-digital age is to practice skills of inferencing and exclusion inherent in repetition of skills-based conceptual learning in contrast to procedural learning alone for generalization of the working memory capacity. Literacy learning is especially rich with such an introduction to concepts, as explained in the study,

THE ROLE OF FICTION IN IMPROVING THE INTELLECTUAL POTENTIAL OF STUDENTS by Rakhmonova Dilfuza MakhmudovnaTeacher of Pedagogy department Bukhara State University.

The researchers say that a child’s passion for reading, and constant interest in reading is formed from experiences in the family. Early exposure determines a child’s internalization of the basic habit of reading. Many teachers guarantee that the success of developing an interest in reading poetic literature among elementary school students depends on the participation of parents in encouraging genre exposure. Children require a “reading text-rich environment” to focus children’s attention not only on the plot but also on the intellectual methods of the language of fairy tales, stories, elegy, and other works of poetic literature. Over time, children develop a preference for literary works and a poetic taste which develops the layers of working memory language. Research has shown that reading works of art always performs cognitive, aesthetic, and educational functions and forms the child’s emotional sphere, moral and aesthetic ideals, views, and attitudes. Knowledge of literature is of great importance for developing a child’s creative inclinations. Reading fiction stimulates the creative imagination, allows the imagination to work, and teaches children to think in images. Reading develops cognitive interests and broadens one’s worldview.

Educators, psychologists, and philologists are worried that in this hyper-digital, post-COVID-19 learning environment, the utilization of books is being replaced by non-literary digital content and computer products. Poetic literature serves as a tool for multifaceted development: it develops memory, speech, and creative imagination, teaches children to think in images, and expands their vocabulary and worldview. Also, figurative memory develops and improves working memory and stability of attention, mental activity depends on it.

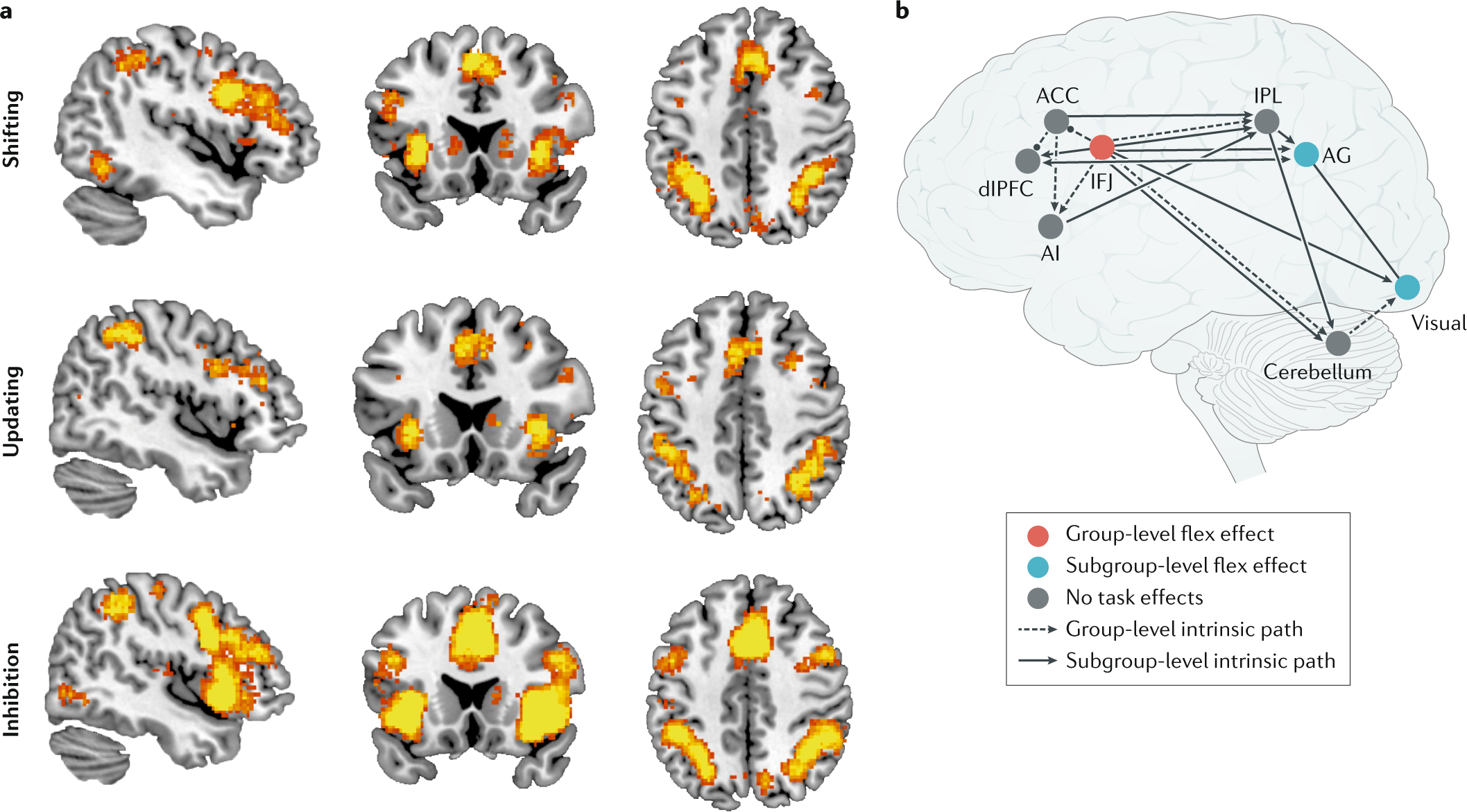

The interaction with literary contexts allows children to develop imagination and hold scenarios in their consciousness, laying the foundation of explorative activity, curiosity, general culture, and knowledge. Then how do working memory components develop further after or parallel to the continuing literacy exposure and interaction? The answer is to then encourage the cooperative functioning of the three core executive functions (inhibition, working memory, and cognitive flexibility), which develop significantly across childhood and well into adolescence (Wiebe & Karbach, 2017). They are excellent predictors of learning outcomes and academic performance (e.g., Johann & Karbach, 2021), and in turn, they are impaired in many developmental and learning disorders (e.g., Barkley, 1997, Brandenburg et al., 2015). The fact that working memory was significantly associated with problem-solving performance confirmed our expectations and is in line with previous research (Greiff et al., 2016, Viterbori et al., 2017).

Schäfer, J., Reuter, T., Leuchter, M., & Karbach, J. (2024). Executive functions and problem-solving—The contribution of inhibition, working memory, and cognitive flexibility to science problem-solving performance in elementary school students. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 244, 105962. investigated the individual contribution of inhibition, working memory, and cognitive flexibility to science problem-solving performance in elementary school children. They found that structural equation modeling showed that working memory and cognitive flexibility individually contributed to problem-solving performance, whereas inhibition did not. Maintaining task requirements and dynamic object relations (working memory) and switching between different problem-solving phases (cognitive flexibility) are essential components of successful science problem-solving in elementary school children. Inhibitory processes may be more relevant in tasks involving a higher degree of interference at the task or response level.

This finding suggests that working memory enables elementary school children to keep track of task requirements, previously applied strategies, and dynamic spatial interdependencies between different task-relevant objects, of which literacy exposure could be a factor in the interdependence of the interaction with cognitive flexibility. These object interdependencies are based on rule-based principles of turning direction and turning speed of connected gears and of ways to stabilize building block constructions (Schäfer et al., 2024a).

Now when we speak about children up to this point, we have been referring to neurotypical learners. For neurodiverse students especially those who may have developmental language disorder, early exposure to literary texts and dynamic spatial play components may not be sufficient to spark the natural nurtured growth of wholistic working memory. To be specific there are verbal short-term memory (vSTM) and verbal working memory (vWM) components that need to also be included in the training of these children for daily life and tasks to be performed independently.

Bachourou, T., Stavrakaki, S., Koukoulioti, V., & Talli, I. (2024). Cognitive vs. Linguistic Training in Children with Developmental Language Disorder: Exploring Their Effectiveness on Verbal Short-Term Memory and Verbal Working Memory. Brain Sciences, 14(6), 580. found in their study that far-transfer memory effects can actually occur for children with DLD (meaning, language therapy can affect vSTM and vWM) in addition to direct and near-transfer memory effects. Far-transfer memory is the ability to apply knowledge or skills acquired in one context to a different context or domain, while Near-transfer memory is the ability to apply existing knowledge in one context to another because of related or identical elements. Both are extremely important components of working memory in language for all children and adults.

These data also show that the combination of different treatment methods and especially the treatment type order during their research may be a significant matter in improving deficient memory abilities in DLD. Specifically, while the children whose intervention was driven by language-first benefited more from receiving the language therapy first improving their verbal STM, the children whose intervention was cognitive-first benefited more from receiving the cognitive therapy first improving their verbal WM. Apparently, performance on vSTM tasks may be more closely related to linguistic demands than that on vWM, and linguistic demands are expected to be more complex and mastered the older the child becomes in the formal educational environment. The memory of language syntax however relies heavily on how developed a child’s cognition which as they found influences their verbal working memory.

With the challenges in linguistic expression, there are also effects of memory underdevelopment or impairment with social functioning within peers and within the learning communities the children belong to. Bullard, C. C., Alderson, R. M., Roberts, D. K., Tatsuki, M. O., Sullivan, M. A., & Kofler, M. J. (2024). Social functioning in children with ADHD: an examination of inhibition, self-control, and working memory as potential mediators. Child Neuropsychology, 30(7), 987–1009. posits that behavioral inhibition and working memory difficulties have been linked with social functioning deficits, but to date, most studies have examined these neurocognitive problems either in isolation or as an aggregate measure of social problems, and none has considered the role of self-control. Thus, it remains unclear whether all of these executive functions are linked with social problems or if the link can be more parsimoniously explained by construct overlap.

Their study consisted of fifty-eight children with ADHD and 63 typically developing (TD) children who completed tests assessing self-control, behavioral inhibition, and working memory; parents and teachers rated children’s social functioning. Examination of potential indirect effects with the bootstrapping procedure used in the study indicated that working memory mediated the relation between group membership (ADHD, TD) and child social functioning based on teacher but not parent ratings. Behavioral inhibition and self-control did not have direct relations with either parent- or teacher-rated social functioning. These findings point to important differences regarding how executive functioning difficulties manifest at school compared to home, as well as the specific executive function components that predict ADHD-related social difficulties.

Another viewpoint on the different manifestations of how working memory manifests between neurodiverse learners versus atypical learners may also be explained through the Attentional Control Theory or ACT, an extension of the Processing Efficiency Theory or PET. The Attentional Control Theory (ACT) posits that, while trait anxiety may not directly impact performance, it can influence processing efficiency by prompting the use of compensatory mechanisms, which apply to both types of learners. The specific nature of these mechanisms, which might be reflective, is not detailed by the ACT.

Cécillon, F., Mermillod, M., Leys, C., Bastin, H., Lachaux, J., & Shankland, R. (2024). The Reflective Mind of the Anxious in Action: Metacognitive Beliefs and Maladaptive Emotional Regulation Strategies Constrain Working Memory Efficiency. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 14(3), 505-530 conducted a study to explore further the relationship of ACT and emotional dysregulation and mental states as they affect working memory.

Participants engaged in two working memory exercises: the digit span task from the WAIS-IV and an emotional n-back task. Their findings indicated that anxiety, metacognitive beliefs, and maladaptive ERSs did not affect task performance but were correlated with increased response times. Several regression analyses demonstrated that a lack of confidence in one’s cognitive abilities and maladaptive ERSs predict higher reaction times (RT) in the n-back task. Additionally, maladaptive ERSs also predict an increased use of strategies in the digit span task. Finally, two mediation analyses revealed that anxiety increases processing efficiency, and this relation is mediated by the use of maladaptive ERSs.

These results underscore the importance of the reflective level in mediating the effects of trait anxiety on efficiency. To explain these differences, the Processing Efficiency Theory (PET) posits that trait anxiety does not necessarily affect performance accuracy (effectiveness) in a task, but rather the speed and cognitive load (efficiency). In other words, for individuals who are predisposed to experiencing anxiety, the cognitive cost and speed of processing a task may be greater [5]. The theory proposes that anxious individuals allocate additional processing resources to implement compensatory strategies designed to improve their performance. According to Owens et al. [6], this advantage is possible for individuals with cognitive resources—such as high working memory, in their study—to compensate for or cope with the negative effects of anxiety. This is how Attentional Control Theory (ACT), an extension of the PET, predicts that the repercussions would be more likely to manifest when cognitive functions requiring attentional control are engaged [7,8]. It is possible that this emotional interference captures participants’ attention more strongly and leads them to make more errors when processing contrasting emotional stimuli. This interpretation may explain the higher frequency of total omission errors compared to emotional omission errors. The emotional alternation of responses may increase the cognitive load and engage participants’ attentional resources more, thereby facilitating the production of responses. These findings highlight the complexity of the interactions among emotions, attention, and decision-making. Commission errors may be influenced by emotional interference, while omission errors may be influenced by the emotional salience of stimuli.

Working memory therefore is directly influenced by an emotional state, especially as seen here when in a negative emotional state of anxiety. This would not be surprising then that the negative emotional states would also affect the rest of the physical body while learners become older and have increasing cognitive demands from their immediate environment.

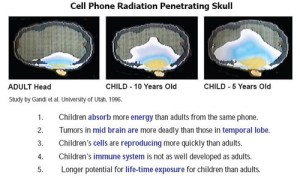

Khandan, M., Ebrahimi, A., Zakerian, S. A., Zamanlu, M., & Koohpaei, A. (2024). Assessment of sleepiness role in working memory and whole-body reaction time. WORK found that even with experts recommending 7–9 hours of nightly sleep for adults and college-aged individuals,3 insufficient sleep poses significant challenges and health risks across all stages of life.6 Young adults experiencing insufficient sleep face both short- and long-term adverse health effects. They also found that lack of sleep affects neural activity in the frontal and parietal cortices, which are important areas for working memory.14 In some studies, problematic sleep, the possibility of negative behavioral consequences such as risk-taking due to the harmful effect on the development of cognitive functions of working memory,15 and the reduction of sleep duration and sleepiness with an increase in calculation error and a significant relationship have been reported by reducing working memory capacity.16 Moreover, with the restriction of sleep time, adolescents showed a decrease in attention, executive function, cognitive memory, positive mood, and greater sleepiness than the control group. In addition, in the control group, the processing speed increased as a result of repeated observation and learning, while in subjects with sleep restriction despite two periods of sleep recovery, their performance was still worse than that of the control group.17 On the other hand, reaction time is believed to be a good indicator of the speed and efficiency of mental processes and is a ubiquitous variable in behavioral sciences.18 In another study on college students, Xie et al. showed that poor sleep quality was related to depressed mood and independently predicted a decline in working memory capacity.36 The results of their study also showed a significant relationship between working memory and reaction time of the subjects. Wilhelm et al. supported the hypothesis that working memory performance is necessary for maintaining arbitrary bindings between stimulus representation and executive response.37 Importantly, Bahner et al. noted in 2006 that working memory can be a predictor of job performance, including this aspect of risk and occupational error while performing the assigned tasks or according to the simple reaction time reported.38

Aside from working memory being influenced by literacy, neurodiversity, emotional states, and sleep, the rest of the physical activity experience of a learner contributes to the development of this EF skill.

Baniasadi, Tayebeh (Marjan), Comparison of Executive Function and Working Memory among Children with High and Low Levels of Physical Activity (June 29, 2024). International Journal of Education and Cognitive Sciences Volume 5, Issue 3, pp 11-17 conducted a cross-sectional design was employed, involving 269 children (128 girls) aged 9 to 12 years from regular schools in Tehran. Participants were selected using convenience sampling. Executive functions were assessed using the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF), working memory using the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children – Fifth Edition (WISC-V), and physical activity levels using the Physical Activity Questionnaire for Children (PAQ-C). Data were analyzed using SPSS version 27, with descriptive statistics calculated and

independent samples t-tests were conducted to compare cognitive functions between high

and low physical activity groups.

Their results indicated significant differences between the two groups, suggesting that higher levels of physical activity are associated with better executive functions and working memory. Specifically, children with high levels of physical activity demonstrated significantly better executive functions (M = 53.67, SD =7.89) compared to those with low levels of physical activity (M = 56.79, SD = 8.22), with a t-value of -3.12 (p = .002). Similarly, working memory scores were higher for children with high levels of physical activity (M = 110.24, SD =14.78) than for those with low levels (M = 104.72, SD = 15.61), with a t-value of 3.58 (p = .0004). By demonstrating significant differences in executive functions and working memory between children with high and low levels of physical activity, this study underscores the importance of promoting physical activity among school-aged children.

Alternately, Zhao, Q., Wang, X., Li, F., Wang, P., Wang, X., Xin, X., Yin, W., Yin, S., & Mao, J. (2024). Relationship between physical activity and specific working memory indicators of depressive symptoms in university students. World Journal of Psychiatry, 14(1), 148 supports the positive correlation between physical activity and increasing working memory efficiency. Physical exercise is closely associated with depressive symptoms and working memory. Previous cross-sectional studies have found that physical activity is significantly negatively correlated with depressive symptoms[23,24], and the higher the level of participation in sports, the lower the risk of depression detection[25]; Physical activity can also improve depressive symptoms by improving working memory. Evidence shows[41] that physical exercise can provide sufficient nutrition and energy to the brain by increasing neurotransmitter content, promoting glial cell regeneration, improving synaptic plasticity, effectively regulating neurotrophic factor concentration, glucocorticoid hormone levels, morphology and structure of specific parts of the central nervous system, as well as the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and at the same time increasing brain plasticity and improving working memory. Furthermore, physical exercise increases the area of grey and white matter in the prefrontal, parietal, and temporal lobes[42], induces structural changes in the hippocampal volume and the vascular system[43], and significantly increases the number of newborn neurons[44], which, in turn, improves working memory capacity.

To conclude, a wholistic working memory capacity is influenced by early exposure to brain EF skill training using literary, physical activity, play, and positive emotional experiences throughout the learner’s lifetime, with specific intervention necessary for neurodiverse learners targeted to develop verbal working memory along with other EF skills.

to many children as soon as their old enough to enter a school-type program. And ending around 9:00 pm may be a conservatitve estimate, especially for middle and high-school aged students. 9:00 is when some finally arrive home to begin their homework or are continuing to work on it because despite their best efforts it stillis not done. The best efforts may even include working with one, two perhaps three different tutors in one evening. What appeared to be parents encouraging natural talents in music or sports has given rise to a hyper-focus on areas of specialization and the building of child prodigies in the arts, athletics or academics. However, very little, if any, of these budding ‘careers’ are related to the child’s school day. Perhaps the long standing problem America faces with education has as much to do with poor schooling as it does with student burn-out. A burn-out that appears to be occuring much earlier and in more extreme ways than senioritis–perhaps now an obsolete term. This critical look at the extrememly scheduled, programmed and packed days of school aged children leaves one questing begging to be asked: What ever happened to having time to play?

to many children as soon as their old enough to enter a school-type program. And ending around 9:00 pm may be a conservatitve estimate, especially for middle and high-school aged students. 9:00 is when some finally arrive home to begin their homework or are continuing to work on it because despite their best efforts it stillis not done. The best efforts may even include working with one, two perhaps three different tutors in one evening. What appeared to be parents encouraging natural talents in music or sports has given rise to a hyper-focus on areas of specialization and the building of child prodigies in the arts, athletics or academics. However, very little, if any, of these budding ‘careers’ are related to the child’s school day. Perhaps the long standing problem America faces with education has as much to do with poor schooling as it does with student burn-out. A burn-out that appears to be occuring much earlier and in more extreme ways than senioritis–perhaps now an obsolete term. This critical look at the extrememly scheduled, programmed and packed days of school aged children leaves one questing begging to be asked: What ever happened to having time to play?

ish-Language Arts New York State Test–a day that has been kept in the back of students’ minds since September. The girls bustle about in their homerooms turning in homework, gathering books and pencils, highlighters and water bottles. Anything within reason that will help them sit anywhere from 90 minutes to 2 hours and 15 minutes answering questions about topics that bear very little relevance in their lives.

ish-Language Arts New York State Test–a day that has been kept in the back of students’ minds since September. The girls bustle about in their homerooms turning in homework, gathering books and pencils, highlighters and water bottles. Anything within reason that will help them sit anywhere from 90 minutes to 2 hours and 15 minutes answering questions about topics that bear very little relevance in their lives.

ion or the practice of physical relaxation, whereas there was no difference between the two groups when measuring changes in concentration and inhibition of distraction. This shows that simple and easy to use interventions can be utilized in the classroom to target and increase student’s sustained attention.

ion or the practice of physical relaxation, whereas there was no difference between the two groups when measuring changes in concentration and inhibition of distraction. This shows that simple and easy to use interventions can be utilized in the classroom to target and increase student’s sustained attention.

youneed to do. You print out your lesson plans and the lay out the work for the morning periods. Another grounding staple of your day, now you know exactly what you planned to say and can see everything you planned to give. Your mind shifts to your students; will she be here today? She’s your most challenging student; feedback flashes through your mind, “Just ignore the behavior; its attention seeking.” “You’re too cold in the classroom; she’s reacting to that.” “She doesn’t like change, and you’re a new teacher.” you for her out of control behavior. What’s the right answer? None of this feedback feels reflective of your experience with this student. You’re at a loss as to what you should do. A part of you wills her to be absent today. 8:00, students walk in right on cue. You look up from the computer and see her with a big smile walk in. You remind yourself to breathe.

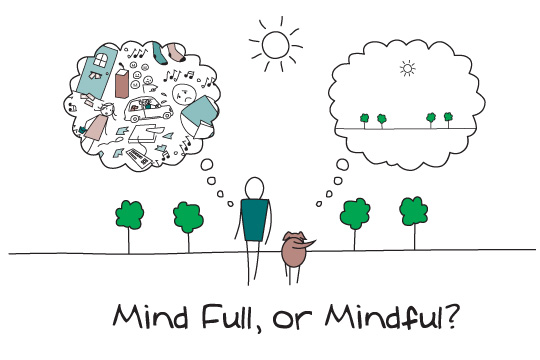

youneed to do. You print out your lesson plans and the lay out the work for the morning periods. Another grounding staple of your day, now you know exactly what you planned to say and can see everything you planned to give. Your mind shifts to your students; will she be here today? She’s your most challenging student; feedback flashes through your mind, “Just ignore the behavior; its attention seeking.” “You’re too cold in the classroom; she’s reacting to that.” “She doesn’t like change, and you’re a new teacher.” you for her out of control behavior. What’s the right answer? None of this feedback feels reflective of your experience with this student. You’re at a loss as to what you should do. A part of you wills her to be absent today. 8:00, students walk in right on cue. You look up from the computer and see her with a big smile walk in. You remind yourself to breathe. you don’t know what you don’t know you need to be able to step outside of yourself and view that self from a different perspective, yet also be able to be aware of yourself in each moment. Enter mindfulness. Dr. John Kabot-Zinn states, “mindfulness means

you don’t know what you don’t know you need to be able to step outside of yourself and view that self from a different perspective, yet also be able to be aware of yourself in each moment. Enter mindfulness. Dr. John Kabot-Zinn states, “mindfulness means

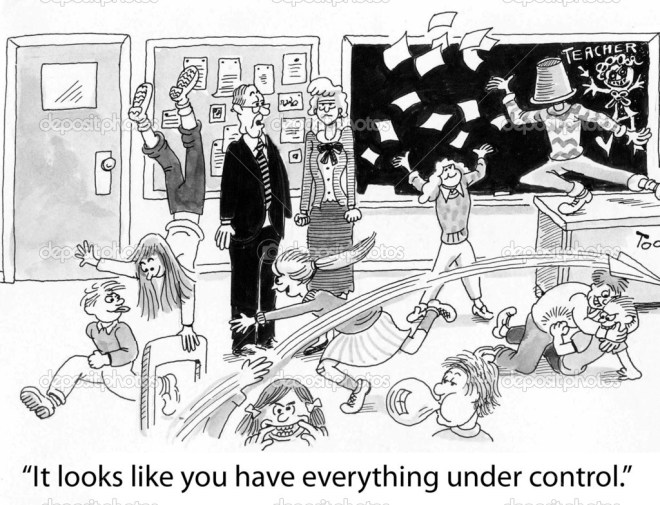

et’s take a snapshot of the current system: schools invest thousands of dollars in curriculums that align to the common core standards, which tout an increase reading and math proficiency. Yet these curriculums are changed yearly because student scores do not increase at the expected rate. Some schools banned use of textbooks and teachers, who have been supposedly taught how to teach are also now expected to create curriculums or piece together a decade worth of rejected curriculums oftentimes for either multiple grades or multiple subjects. And within this disorganized system, children who struggle to learn within a traditional classroom, for reasons neuropsychologists are still trying to determine, are expected to adapt and learn in the same way, at the same rate with the same retention as their typically developing peers. Administrators and teachers alike, are allowed to overlook this since their academic background never afforded them an opportunity to learn nor required it of them. Yet the perfectly typical students with atypical brains become the ones punished for this oversight. Not only do teachers have decreased expectations, which leads to decreased effort; being labeled as special ed is shown to have a negative impact on self-esteem.

et’s take a snapshot of the current system: schools invest thousands of dollars in curriculums that align to the common core standards, which tout an increase reading and math proficiency. Yet these curriculums are changed yearly because student scores do not increase at the expected rate. Some schools banned use of textbooks and teachers, who have been supposedly taught how to teach are also now expected to create curriculums or piece together a decade worth of rejected curriculums oftentimes for either multiple grades or multiple subjects. And within this disorganized system, children who struggle to learn within a traditional classroom, for reasons neuropsychologists are still trying to determine, are expected to adapt and learn in the same way, at the same rate with the same retention as their typically developing peers. Administrators and teachers alike, are allowed to overlook this since their academic background never afforded them an opportunity to learn nor required it of them. Yet the perfectly typical students with atypical brains become the ones punished for this oversight. Not only do teachers have decreased expectations, which leads to decreased effort; being labeled as special ed is shown to have a negative impact on self-esteem. t means to have a disability, the strengths and weaknesses associated with that disability and strategies in which that student can overcome barriers within academic institutions in order to find success. However, this is next to impossible when teachers are not required to learn more than simple terminology associated with educational disabilities such as IEP, learning disability, and maybe related services. In 2013,

t means to have a disability, the strengths and weaknesses associated with that disability and strategies in which that student can overcome barriers within academic institutions in order to find success. However, this is next to impossible when teachers are not required to learn more than simple terminology associated with educational disabilities such as IEP, learning disability, and maybe related services. In 2013,