In young children, the schema of their quality world usually revolves around a caregiver or a person who they consider as important in the development of their identity. Their interests initially mimic from imagining that they are versions of the adults they are surrounded by until they are exposed to wider environments, peers, language, media, and then a wholistic interest database emerges from the conglomeration and exposure.

It also makes sense that the younger the child, the more questions they ask. Rarely would you find a child between the ages of 3-5 years come into contact with adults who have set values or biases of themselves concerning what’s ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ around the way they perceive the world. This type of mental flexibility, of mixing and matching new, or new-old ideas in their youth is also directly proportional to the physical activity that they engage in. The pushing of limits of their physical capacities around places that are close to the natural world like garden parks, or places that have been landscaped for the socialization of little people like urban parks are indicators of their levels of mindful curiosity.

It certainly becomes less correlational when children become older, the degree or type of questions with physical movement. The overt questions may turn into musings and conformity is usually expected when school-age commences. Physical movement is timed if the child is not involved in organized sports or games. Just the same, however, the degree of flexibility in these minds depends on the environment they take in, and the imagination that is left from viewing the world from their youth. Martinez and Riba’s 2021 study, Cognitive Flexibility in Schoolchild Through the Graphic Representation of Movement postulates that Neuroconstructivism is the progressive complexity of mental representation over the course of cognitive development and the role of the graphic representation of movement in the transformation of mental schemas, cognitive flexibility, and representational complexity.

They also discuss that In this differential trajectory, mental representation is a key element for cognitive development and for understanding the emergence of child drawing, and changes thereof, as a graphic representation of internalized models of reality (Sirois et al., 2008). A child’s drawing is the first marker that enables the study of mental representation as an external manifestation of internalized reality, by showing what is known about it.

Moreover, events are naturally more attractive than objects, and their foremost feature is their movement. Therefore, part of the content of the first mental representations turns around the identity of events, objects, and people, and their movement and position, which forms the basis of the dynamic representations produced. The first external representative manifestation is the child’s scribble, in which the action of the drawing already contains expressive and representational meanings relating to shapes, movements, and emotions (Quaglia et al., 2015), even if there is no real figure that relates to a meaningful movement for representational purpose.

Such cognitive flexibility is what drives competition in a crowd. The narratives that may have been handed down from authority figures that were used to set ‘safety’ limits, such as limiting or eliminating outdoor time due to the location of where the child resides, or in this recent case the pandemic, inadvertently have pared down the curiosity factor toward the external influences. Subsitutions by devices and programs on the web were meant to digitize the parallel experience of the world beyond the home, however, without the multisensorial inundation of an experience, the ideas being written are almost dream-like. They may be able to describe a forest of trees in a contextual litany of facts, but ask them about the experience and then they are puzzled.

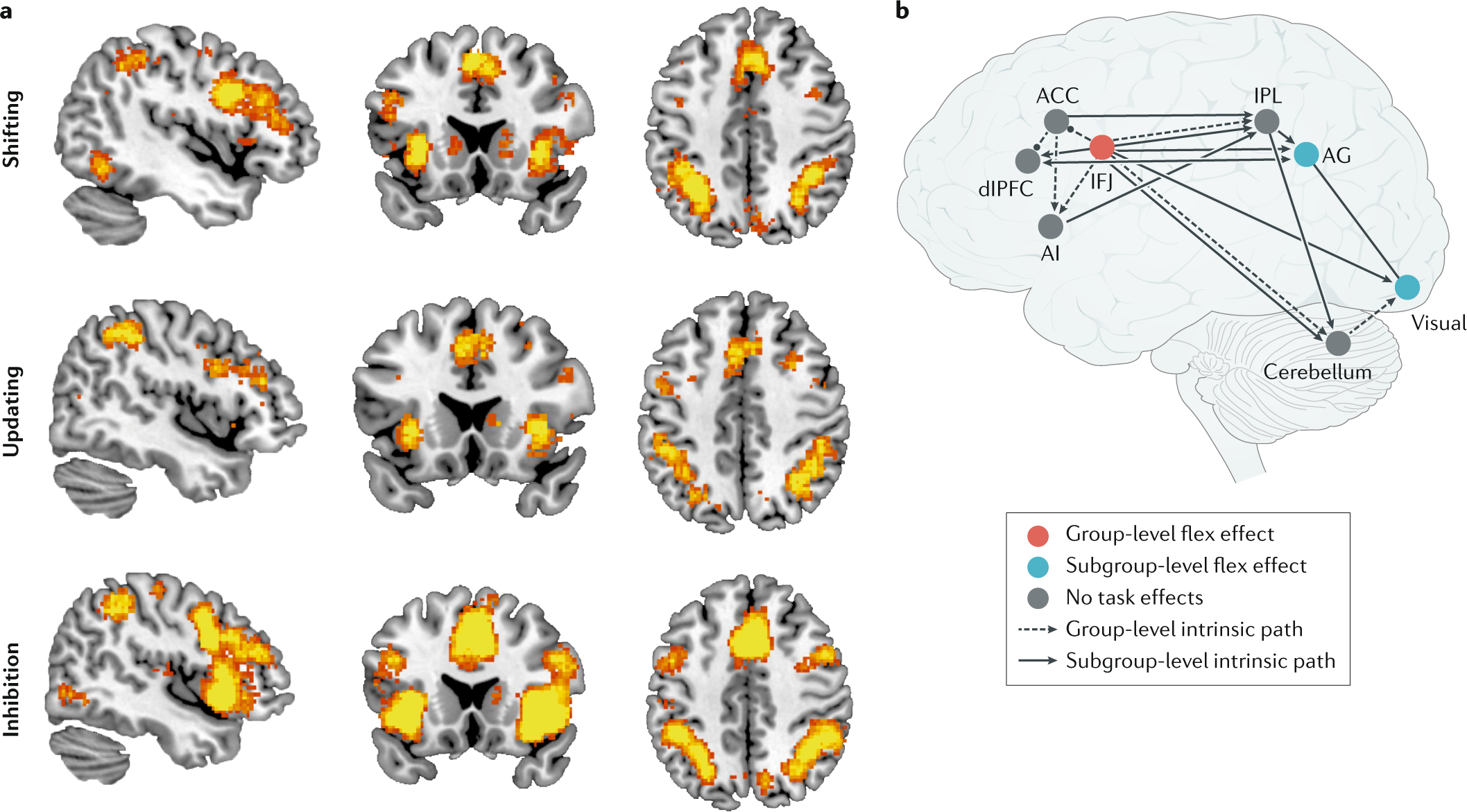

So do you make up for lost cognitive flexibility time for children? Or for yourself as a person of structure and routine? The answer is no. It is more important to make active choices to be exposed to the internal and external worlds that are immediate and to ensure that physical movements are consciously added in a 24 hour period than to make up for the over a year of standing still. Scientific studies have isolated the executive functions that aim at cognitive flexibility, which include the abilities to shift one’s thinking (flexibility), updating the learning that has been made based on the thinking shift (working memory), and response inhibition. In Uddin’s 2021 study, Cognitive and behavioural flexibility: neural mechanisms and clinical considerations she explains the core processes in thinking flexibility with this figure:

Fig. 1: Core cognitive processes and brain network interactions underlying flexibility in the human brain. From: Cognitive and behavioural flexibility: neural mechanisms and clinical considerations

These brain maps were established with the use of automated meta-analyses of published functional neuroimaging studies can be conducted with Neurosynth, a Web-based platform that uses text mining to extract activation coordinates from studies reporting on a specific psychological term of interest and machine learning to estimate the likelihood that activation maps are associated with specific psychological terms, thus creating a mapping between neural and cognitive states. In the study, Neurosynth reveals that brain imaging studies including the terms ‘shifting’, ‘updating’ and ‘inhibition’ report highly overlapping patterns of activation in lateral frontoparietal and mid-cingulo-insular brain regions, underscoring the difficulty of isolating the construct of flexibility from associated executive functions.

This means that cognitive flexibility is an activity that requires the whole brain, and if that is the case, then it requires a complete human experience. In an article by Sahakian, et. al in the World Economic Forum site called, Why is cognitive flexibility important and how can you improve it? they indicate that Cognitive flexibility provides us with the ability to see that what we are doing is not leading to success and to make the appropriate changes to achieve it. Flexible thinking is key to creativity – in other words, the ability to think of new ideas, make novel connections between ideas, and make new inventions. It also supports academic and work skills such as problem-solving.

They also write that cognitive flexibility can also help protect against a number of biases, such as confirmation bias. That’s because people who are cognitively flexible are better at recognizing potential faults and difficulties in themselves and using strategies to overcome these faults. See their table below showing the flexibility representations:

How do we become adept at choosing to be flexible especially in situations that give little determination of what we can control? Aside from practicing the principles of evidence-based psychological therapy which allows people to change their patterns of thoughts and behavior (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy or CBT), Structure learning has been proven to be potentially another way. It has been described as a person’s ability to extract information about the structure of a complex environment and then decipher initially incomprehensible streams of sensory information via the process of elimination. This specific type of learning taps into the similar frontal and striatal brain regions as cognitive flexibility, thus exposure and practice are the keys to successful learning.

Go forth, be human, and explore!

ion or the practice of physical relaxation, whereas there was no difference between the two groups when measuring changes in concentration and inhibition of distraction. This shows that simple and easy to use interventions can be utilized in the classroom to target and increase student’s sustained attention.

ion or the practice of physical relaxation, whereas there was no difference between the two groups when measuring changes in concentration and inhibition of distraction. This shows that simple and easy to use interventions can be utilized in the classroom to target and increase student’s sustained attention. youneed to do. You print out your lesson plans and the lay out the work for the morning periods. Another grounding staple of your day, now you know exactly what you planned to say and can see everything you planned to give. Your mind shifts to your students; will she be here today? She’s your most challenging student; feedback flashes through your mind, “Just ignore the behavior; its attention seeking.” “You’re too cold in the classroom; she’s reacting to that.” “She doesn’t like change, and you’re a new teacher.” you for her out of control behavior. What’s the right answer? None of this feedback feels reflective of your experience with this student. You’re at a loss as to what you should do. A part of you wills her to be absent today. 8:00, students walk in right on cue. You look up from the computer and see her with a big smile walk in. You remind yourself to breathe.

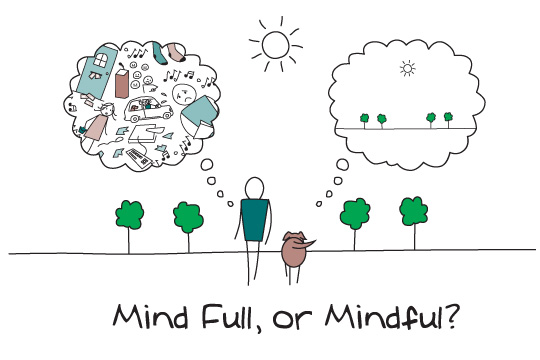

youneed to do. You print out your lesson plans and the lay out the work for the morning periods. Another grounding staple of your day, now you know exactly what you planned to say and can see everything you planned to give. Your mind shifts to your students; will she be here today? She’s your most challenging student; feedback flashes through your mind, “Just ignore the behavior; its attention seeking.” “You’re too cold in the classroom; she’s reacting to that.” “She doesn’t like change, and you’re a new teacher.” you for her out of control behavior. What’s the right answer? None of this feedback feels reflective of your experience with this student. You’re at a loss as to what you should do. A part of you wills her to be absent today. 8:00, students walk in right on cue. You look up from the computer and see her with a big smile walk in. You remind yourself to breathe. you don’t know what you don’t know you need to be able to step outside of yourself and view that self from a different perspective, yet also be able to be aware of yourself in each moment. Enter mindfulness. Dr. John Kabot-Zinn states, “mindfulness means

you don’t know what you don’t know you need to be able to step outside of yourself and view that self from a different perspective, yet also be able to be aware of yourself in each moment. Enter mindfulness. Dr. John Kabot-Zinn states, “mindfulness means