As much as there have been many suggestions and studies on how to cope with the pandemic using multi-modal means, such as apps, vitamins or physical exercise, or even new hobbies and food adventures. And that is on the upside of things. Coping skills when the cards are stacked against your favor hyper focuses on survival from moment to moment when the brain is overloaded and tasked with overchoice.

Multi-million-dollar industries have been built on people’s pursuits on the fountain of youth and keeping the brain young or at least to match the youthful vigor of how the body should feel. Emotionally despite our wanting for vigor, we are brought back to realization by our brain’s level of resources or how to retrieve it as the amygdala automatically pushes past the suggestion of pain or difficulty when basic needs are of the essence.

Caring for the brain’s emotions are interdependent on the human capacity for social cognition when reading body language and expressions. And in the stressful pandemic times, adaptive social behavior and mental well-being also require inferring the absence of emotional content. Of relevance during exceptional events such as the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic involving social distancing and isolation as well as higher levels of anxiety but also, requiring intact social communication and empathy. (Sokolove et al, 2020)

When one is required to maintain social distance and/or uses PPE while interacting with another, the interplay between the amygdala and insula is elevated as it contributes substantially to the processing of social signals that convey emotionally neutral information, underwriting a fundamental yet underestimated component of adaptive social cognition and behavior. The absence of stimulatory emotion presents a difficulty of processing in the bond communication between the amygdala and insula with the ability to infer the

absence of emotion in body language, including with the processing within the amygdala and insula have been associated with emotion perception. Ultimately, when caring for the brain’s health scanning other people’s words and delivery are what is needed for homeostasis.

So, the brain begins searching for alternates in reading and writing ’emotion’ in times of crises to maintain itself. Depending on the coping mechanisms embedded within the connections, physical and/or psychological experience that binds with an external event, this one being the lack of neurotypical emotion perception could potentially ripple into pre-existing trauma. There are growing indications that these trauma-exposed individuals show

neural alterations, even in the absence of clinical symptoms and tasks requiring the regulation of emotions and impulses seem to be particularly affected. Sabrina Golde et.al

studied 25 women (mean age 31.5 ± 9.7 years) who had suffered severe early life trauma but who did not have a history of or current psychiatric disorder, with 25 age- and education-matched trauma-naïve women by utilizing fMRI study investigated response inhibition of emotional faces before and after psychosocial stress situations in 2019. In both groups, nontraumatic stress significantly impaired response inhibition of fearful facial expressions but did not affect inhibition of happy or neutral stimuli. When inhibiting responses to fearful faces under stress, women who had experienced severe and multiple traumatic events before the age of 18 demonstrated a decreased brain signal in the left inferior frontal gyrus in the frontal lobe, but a marginally increased signal in the right anterior insula (between the frontal and temporal lobes) compared to trauma-naïve control subjects.

They also discovered that in trauma-naïve control subjects only, the inferior frontal gyrus activation was linked to a lower rate of stress-induced false alarms, whereas in women who had experienced severe and multiple traumatic events before the age of 18, insula activation was linked to a higher number of false alarms.

Of course, that begs the question, would brain health be different between a male brain in comparison to the female brain? Are brains not simply just as generic as other parts of the body such as the skeletal and muscular systems? Would the same study above if applied to men render equitable results as the women have displayed? Perhaps, as brain function is dependent on synapses and stimuli response. However as unique as every individual is, the responses can and will be varied according to the emotional pairing, regardless of assigned biological sex.

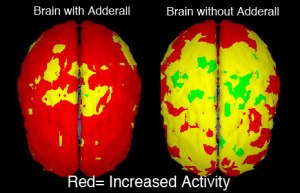

After all neuroplasticity happens to people, mostly in the background, positive or negative. The learning experience is constantly evolving, including in what is automatic such as driving, to the more complex tasks such as learning a new skill or trade. Yet in the viewpoint from a healthy brain, neuroplasticity would support neural pruning at every stage of life: keeping only the connections that are meaningful and consistently used for an end goal while allowing brain real estate to grow for additional new experiences to bind. If, however the exposure is constantly negative neuroplasticity such as death, destruction, or violence, the brain’s stress levels are increased thus decreasing overall expanded connections and brain weight.

Sandra Racionero-Plaza, et al., found in their research article, “Architects of Their Own Brain.” Social Impact of an Intervention Study for the Prevention of Gender-Based Violence in Adolescence sought to review the social impact of psychology in the field of teen gender violence from participants in the MEMO4LOVE project comprised 126 adolescents attending three different high schools in Barcelona (Spain). The aim was to report on the potential social impact achieved by an intervention study consisting of seven interventions on the preventive socialization of gender violence, with specific interventions focused on seven different topics. Part of the intervention were dimensions of the influence of the dominant coercive discourse in adolescents’ sexual-affective life, accompanied by egalitarian dialogue with the adolescents on how to break free from such discourse and thus avoid violence in sporadic or stable sexual-affective relationships. Below is what they found:

1) The adolescents who took part in these interventions reported developing critical consciousness regarding the presence of the dominant coercive discourse in society and in their lives. The greater the transformation of peer interactions, the greater the prevention of gender-based violence victimization.

2) It is necessary that intervention strategies in education provide adolescents with tools that enable them to be more critical about violence in society. Interventions provided them with cognitive tools to better analyze their own and others’ sexual-affective thinking, emotions, and behaviors in ways that favor the rejection of violent males and violent sexual-affective relationships

3) Change in preferences and attraction, with greater rejection of violent men and enhanced attraction toward egalitarian masculinities. It is significant to be aware of the dominant coercive discourse, but what is even more fundamental is to change the response of attraction toward men with violent attitudes and behaviors; that is what will make a difference in terms of preventing gender-based violence victimization.

Society therefore continues to impact the neuroplasticity quality with our degrees of interaction with it. Aside from gender and age groups, it is of significance to mention that brain health across races also have complex layers affecting neuroplasticity. In the research article, Insights From African American Older Adults on Brain Health Research Engagement: “Need to See the Need” Soshana Bardach, et al., posited that African Americans (AAs) have an elevated risk of developing dementia, yet are underrepresented in clinical research. In order for the 21 AAs aged 35-86 years to agree to be part of the study, the researchers had to ensure that the facilitators were AA from their community, laying out clearly and plainly the methodology that would be used to gather data which is called Photovoice, and to be transparent about the reasons behind the data gathering.

The use of Photovoice in data collection is a community-based, participatory-action research methodology, centered on the premise that sharing perceptions and experiences through photography and discussion leads to an awareness and understanding of relevant issues (Harley et al, 2015) It was through this method that the discussion of brain health research among AAs highlighted several barriers to participation and corresponding strategies for addressing the identified barriers and encouraging engagement. The barriers and solutions were in the areas of (a) mistrust stemming from historical mistreatment and reinforced by contemporary injustices, (b) avoidance and fear of acknowledging problems such as being afraid of what they may find out or not wanting to know as barriers to seeking a diagnosis, and (c) seeing the risks of research, but not the need as they anticipate potential unpleasant aspects of research participation were more tangible than the benefits.

This then brings us to consider that brain health is not only a result of positive neuroplasticity but a contiguous history of sustainable emotions stemming from society and communities. The deterioration of the brain affected by genetics is also sped up by neurochemicals that inflame the stress response on a consistent basis thus making recovery to a biologically sound baseline unattainable. Anti-declining the brain, simply put, is to bring it to a social balance. An immediate way is to encourage pro-social behaviors between humans and/or animal species. Pro-social behaviors—actions that help others, often without regard to whether they directly benefit us—are vital for social cohesion. (Lockwood, et al, 2020) The idea is that to do acts that benefit other people, we first must learn what actions in the world will lead to something rewarding and positive happening to them, all processed in the anterior cingulate cortex of the brain. When we perform an action, and it results in a reward for another person, it is easy to imagine ourselves in their shoes and vicariously experience what it would be like to get a similar reward ourselves.

If there are limited opportunities for vicarious learning or pro-social behaviors, such as when in a global crises, how can balance be achieved? Ironically, Polyphenol-Rich Interventions are in order to influence the sensitivity of natural neurotransmitters and adjust levels naturally. Polyphenol compounds, such as flavonoids, phenolic acids and tannins, are found in varying concentrations in a range of plant-based food sources (e.g., legumes, fruit, vegetables, herbal extracts, spices, coffee, tea and cocoa), and their effects on human health have drawn considerable attention. (Ammar, et al 2020). It is the self-socializing method by virtue of self-care that supports choices of the quality of brain health. At this particular juncture, the use of the human amygdala is its response to other emotionally significant stimuli beyond threat, including positive or reward information, but also novelty and non-emotional salient stimuli with personal impact or goal-related significance. This diversity of response patterns has led to recent theoretical accounts proposing that the amygdala may actually encode the “relevance” of events, which is determined by the goals, needs, or values of the individual, in a context-dependent manner. (Guex et al, 2020) This account accords with psychological theories, such as the component process model of emotional appraisal as would in patterns of self-socialized self-care.

The anterior cingulate cortex and the amygdala would need support when communicating emotions-bound signals to each other. It is with the subcortical structures of the basal ganglia (BG) and the cerebellum that support multiple domains including affective processes such as emotion recognition, subjective feeling elicitation and reward valuation. By regulating

cortical oscillations to guide learning and strengthening rewarded behaviors or thought patterns to achieve a desired goal state, these regions can shape the way an individual processes emotional stimuli. (Pierce J, et al 2020) In essence, no matter how much objective data could be presented to standardize the ideal brain health for a given time frame, developmental stage, race or gender, the conclusion will rest upon every individual’s experience or norm of how their brains are in status quo or if they are on polar opposites. Whatever the case may be, brain health is essential for quality of life.