It is 7:30 a.m.; you’re in your classroom, preparing the materials for the day. The classroom is quiet except for the music in the background–it’s become a routine you started a few weeks back to ground you in the day. No one ever told you teaching would be THIS hard. How does time pass by simultaneously both lightening speed and a snail’s pace? It’s your sixth week of teaching already. You glance up at the clock 7:32. Relief sweeps over you! 28 more minutes until students arrive enough time to finish what  youneed to do. You print out your lesson plans and the lay out the work for the morning periods. Another grounding staple of your day, now you know exactly what you planned to say and can see everything you planned to give. Your mind shifts to your students; will she be here today? She’s your most challenging student; feedback flashes through your mind, “Just ignore the behavior; its attention seeking.” “You’re too cold in the classroom; she’s reacting to that.” “She doesn’t like change, and you’re a new teacher.” you for her out of control behavior. What’s the right answer? None of this feedback feels reflective of your experience with this student. You’re at a loss as to what you should do. A part of you wills her to be absent today. 8:00, students walk in right on cue. You look up from the computer and see her with a big smile walk in. You remind yourself to breathe.

youneed to do. You print out your lesson plans and the lay out the work for the morning periods. Another grounding staple of your day, now you know exactly what you planned to say and can see everything you planned to give. Your mind shifts to your students; will she be here today? She’s your most challenging student; feedback flashes through your mind, “Just ignore the behavior; its attention seeking.” “You’re too cold in the classroom; she’s reacting to that.” “She doesn’t like change, and you’re a new teacher.” you for her out of control behavior. What’s the right answer? None of this feedback feels reflective of your experience with this student. You’re at a loss as to what you should do. A part of you wills her to be absent today. 8:00, students walk in right on cue. You look up from the computer and see her with a big smile walk in. You remind yourself to breathe.

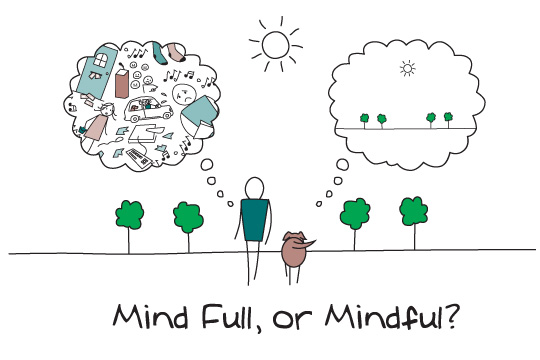

You don’t know what you don’t know. This idea feels almost like a theme in the field of education, administrators and educators alike–new educators in particular. It seems that the idea of not knowing or being told you don’t know is often received defensively as an offense. When in fact, it is actually more akin to a free pass for commonly made mistakes or assumptions–on made by teachers and administrators–and an invitation to learn. However, the willingness to learn means admitting to not knowing or worse: imperfection. Yet this ability to stand back and look with a critical and personal lens at the breadth of knowledge possessed and honestly admit that gaping holes exist does not come easily to many. Perhaps, because this exercise in humility requires both metacognition and mindfulness.

Metacognition according to Dr. Richard Guare and Dr. Peg Dawson is “the ability to take a birds eye view of oneself in a situation. It is the ability to observe how you problem solve. It also includes self-monitoring and self-evaluative skills (e.g. asking: “How am I doing?” or “How did I do?”) In order to fully be able to accept, acknowledge and understand that  you don’t know what you don’t know you need to be able to step outside of yourself and view that self from a different perspective, yet also be able to be aware of yourself in each moment. Enter mindfulness. Dr. John Kabot-Zinn states, “mindfulness means

you don’t know what you don’t know you need to be able to step outside of yourself and view that self from a different perspective, yet also be able to be aware of yourself in each moment. Enter mindfulness. Dr. John Kabot-Zinn states, “mindfulness means

maintaining a moment-by-moment awareness of our thoughts, feelings, bodily sensations, and surrounding environment. In order to participate in these states of being, one needs intentionality, practice and an honest self-view, which is easier said than done, especially within institutions in which normed rolls have been established.

Learning, empathy and change cannot take place when conversations are entered into with established or implied hierarchical relationships, for example, the teacher and the learner. While exceptions exist, many institutions of education have an established dichotomy of superiors and inferiors. These can found throughout the school in different capacities. Yet, rather than promote an environment for learning by sharing knowledge and openly celebrating strengths and finding others to support weaknesses; a fake it until you make it attitude emerges, defenses are on high-alert and learning fails to take place.

Imagine how a conversation between an educator and administrator would go if both parties came to the table, coming clean about their knowledge gap.

The administrator would have to own up to the fact that she has very little knowledge about what happens on a daily basis in the classroom that may be enhancing or inhibiting classroom learning. A new educator may need to admit to not knowing the difference between off-task behaviors because a child is bored versus one who simply doesn’t understand. The point is both parties would be entering into a conversation with an honest self-view and the intention to truly listen and learn from the other.

This begins by admitting that you don’t know what you don’t know. People are imperfect, make mistakes, react to situations without thinking and often times hold others responsible for events they had just as much stake in. Inevitably it is easier to stay on the surface of one’s thinking, examine others but never oneself with a critical lens and turn off an awareness to oneself and the environment in which he is in. If this were not the case, “Ignorance is bliss,” would never have been excavated from Thomas Gray’s poem, “Ode on a Distant Prospect of Eton College,’ written in 1742 and still commonly used today.

However, through that course of thinking, much is lost: personal growth, human connection and most importantly systemic change. So stop and think. Step outside of your mind so often on autopilot. What do you see? Ask yourself, “How am I doing today?” Do not leave this answer constrained to the cursory “good” or “fine” or related to your job. Dig deep and ask yourself, “How. Am. I. Doing. Today?” Stop.

This time, don’t think. Feel. Let your body become fully aware of the sights, sounds, and smells, physical sensations that currently surround you know. Ask yourself again, “How am I doing today?” Stay outside of your mind. Breathe. Slowly. In and out. Again. In and out. Again, in and out.

Now ask yourself, “How did I do today? Could I have done better?”

What don’t you know, that you don’t know? Imagine the possibilities if you did.